The Bill Comes Due

I'd put in some work writing this out in the fall but couldn't find a home for it.

I wrote this piece last fall and shopped it around a bit, but it seemed to fall in an odd spot between budget and national security publications. Rather than let it completely go to waste, I’m posting it here. It’s about 7 months old at this point, but still might be interesting for anyone focused on US defense spending and potential fiscal consolidation.

The Bill Comes Due – Servicing the National Debt and Implications on National Security Spending

“Do not accustom yourself to consider debt only as an inconvenience; you will find it a calamity.”

—Samuel Johnson

“Interest works night and day; in fair weather and in foul. It gnaws at a man’s substance with invisible teeth.”

—Henry Ward Beecher

Over the past few months, government borrowing costs in the United States have risen rapidly, signaling the end to a period of cheap government borrowing. This shift will have a significant impact on the trajectory of federal spending over the next decade. Since the turn of the century, the United States government has operated in an extremely accommodating fiscal environment featuring low inflation, low interest rates, and, most importantly, low costs to service the national debt. This created a situation where the government could generally act fairly freely with regard to taxes and spending. As such, despite some gestures towards fiscal consolidation such as the Budget Control Act of 2011 or the recently passed Fiscal Responsibility Act, the core drivers of the national debt – rising spending on entitlements due to an aging population and tax levels inconsistent with total obligations – remained unaddressed. This lax fiscal environment has allowed significant spending to flow into the Department of Defense, the intelligence community and other parts of the national security establishment following 9/11 and then throughout the wars that followed. However, since COVID, the fiscal grounds upon which the government operates have begun to shift. Rising inflation has forced the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates and the cost to sustain the government’s debt is beginning to expand rapidly. If these conditions persist, there will be pressure on Congress and the White House to enact serious fiscal consolidation. Any such proposal will have serious ramifications on national security spending and advocates should begin preparing arguments to protect critical investments across the defense, intelligence and homeland security arenas. In order to understand what these reductions may look like; it is worth reviewing past periods of fiscal consolidation in order to understand the potential outcome going forward.

The Fiscal Situation

The fiscal story of the 21st century is one of lax fiscal conditions accommodating US government policy making. The dollar’s status as the reserve currency has provided the USG with significant demand for US debt and it has met the demand. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, the total debt held by the public has grown rapidly from just under $3.7 trillion in January of 2000 to just shy of $24.7 trillion in January of 2023. Looking at gross debt as a share of GDP, the story is much the same, though due to high inflation the value of the debt as a percentage of GDP peaked in 2020 at 134% and has since declined to “only” 118%. At the same time, due to demand for dollars and low interest rates, the cost of servicing the debt remained remarkably low. Despite the increases in the size of the debt, interest expenditures rose only slowly, going from roughly $355 billion in January 2000 to $584 billion in January of 2020. However, since COVID, those conditions have changed, and interest expenditures are rising rapidly. As those costs grow, the debt will balloon even further, creating pressure on the government to act.

Data source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Federal government current expenditures: Interest payments [A091RC1Q027SBEA], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/A091RC1Q027SBEA, August 31, 2023.

Given the passage of the Fiscal Responsibility Act, which would save roughly $1 trillion if associated commitments are enacted over the next decade and the recent decline in debt as a percentage of GDP, one could be led to believe that the debt was well in hand going forward. This is sadly, not the case. Absent any changes to existing policy, the debt is forecast to expand rapidly over the next decade as inflation slows and entitlement spending ramps up as the Baby Boomer generation continues to exit the workforce. The Congressional Budget Office’s most recent projections have their recording of debt held by the public rising from $27.4 trillion for FY 2024 to $46.7 trillion in FY 2033. Similarly, they have their version of debt held by the public rising from 100.4% to 118.9% over the same time period. In many ways this forecast undercounts the likely debt over the period, as it assumes that various tax breaks enacted under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) that are scheduled to expire over the next few years will do so. According to the Committee for a Responsible Budget, extending all of the provisions in the TCJA would add an additional $3.3 trillion to the debt, wiping out the potential savings from the Fiscal Responsibility Act.

What Would a Potential Response Look Like?

All of this is likely to create conditions that force actual fiscal consolidation by the United States government. While it is possible that this Congressional fiscal fight will be resolved in a manner to address this, it is more likely that conditions will worsen over time such that the period after the 2024 Presidential election will be the period within which action is taken. While the main drivers of the growth in the debt are the aging population and associated entitlement spending, as well as an ongoing unwillingness to grapple with the implications of 20 years’ worth of federal tax reductions, spending on national security is not going to be immune from any future debt reduction exercise. Indeed, the last time there was a period of sustained, borrowing-cost driven deficit reduction was the 1990s which saw massive cuts to DoD as part of the post-Cold War “peace dividend”. Geopolitical conditions are now vastly different but given how significant a percentage of discretionary spending goes towards national security and the potential Congressional coalitions that might be called upon to pass such a package, national security spending could expect a significant near-term haircut or, at best, severely attenuated growth going forward.

There were three significant deficit reduction bills passed during the 1990s that are potentially useful historical analogs for considering what potential future deficit reduction could look like, should it be able to get through Congress. Two of the bills contain a mix of spending reductions and tax increases, while the third combined a relatively small tax cut with larger retrenchment of federal spending. Depending on the electoral outcome in 2024, the composition of a deficit reduction bill may reflect more of the third bill than the second bill. All of the figures from the below comparison comes from work by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP).

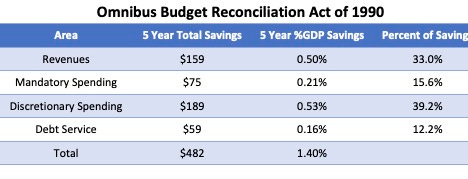

The Omnibus Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1990

Data from author’s calculations, CBPP data and CBO data.

This legislation was supported by a Republican President (George H.W. Bush) and a Democratic Congress. Notably, this is the legislation that prompted President Bush to break his “no new taxes” pledge. However, looking at it from a fiscal perspective, it was fairly successful. The legislation combined cuts to both mandatory and discretionary spending with significant tax increases (though revenue increases only accounted for one-third of the savings). The result was almost a reduction of the budget deficit by 1.4% of GNP. Adoption of similarly ambitious legislation in FY 2025 would reduce the deficit over five years by approximately $2 trillion (based on economic and budget projections from the CBO and the authors own calculations), with a ten-year savings likely significantly higher (due to compounded savings from reduced debt service payments over this time period). Notably, the spending reductions were from a mix of specific program cuts to non-defense activity and the enforcement of budget caps with the threat of sequestration should spending rise above the levels laid out in the legislation.

From a national security perspective, the creation of extended budget caps and the threat of sequestration will call to mind the impact of the Budget Control Act (BCA) of 2011, which led to ongoing brinksmanship over spending from 2011 through to 2021. Interestingly, in the same way that DoD was able to rely on Overseas Contingency Operations spending to ameliorate some of the impact of the BCA, the OBRA of 1990 included exemptions for spending related to operations Desert Shield & Desert Storm. That being said, the implications for spending levels are considerable.

Overall, reducing discretionary spending by roughly $857 billion over five years (a current-dollar value roughly concurrent to the reduction in spending in the 1990 bill) would likely require significant cuts to both defense and non-defense spending. National security spending is, as of FY 2022 – the last year for which actuals are available, is just over 45% of discretionary spending (45.2%). Should there be a proportionate reduction in spending between the two accounts, national security spending would need to be reduced by $389 billion over five years, an annualized rate of $78 billion. Against the FY 2023 figures, this would require a cut of 9.7% in real terms.

Cuts of this scale would need to be accomplished through a mix of year-over-year reductions and limiting spending growth. One easy option to accomplish some of this would be for Congress to enforce the caps and associated restrictions in the FRA, which the Committee for a Responsible Budget has highlighted would save an additional $555 billion over the course of ten years.

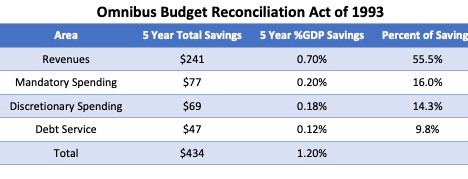

The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993

Data from author’s calculations, CBPP data and CBO data.

The 1993 OBRA was another major deficit reduction package, only this was done under the Clinton administration with unified Democratic control of government. Again, this included a mix of spending cuts and revenue increases, though the overall package was much more heavily weighted towards tax increases than the 1990 OBRA. This package was also precursor to the 1994 election that finally ended Democratic control of the House of Representatives following forty years in the majority. It is unfortunate that the political ramifications of both this legislation and the 1990 OBRA continue through to today as both bills were successful in continuing to drive significant reductions to the deficit. The 1993 OBRA reduced the deficit by roughly 1.2% of GDP over 5 years and the cumulative effect of these bills, alongside the third bill (the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 and Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997), set the stage for a radically improved fiscal position by the end of the 1990s. Whereas, according to CBO data, in FY 1990, the government had been running a deficit equal to 3.7% of GDP, by FY 2000 it was running a surplus of 2.3%.

In terms of national security implications, the heavy emphasis on revenue increases in the 1993 act would be less damaging than a bill modeled after the 1990 OBRA. In today’s terms, legislation of similar ambition would see a total reduction of deficits by $1.9 trillion over five years, with the bulk of the savings coming from increased revenue. In this scenario, discretionary spending would only need to be reduced by $299 billion over five years, a significantly easier goal than the numbers seen in the 1990 OBRA. This lower figure would still require a reduction of roughly 3.4% from current spending levels.

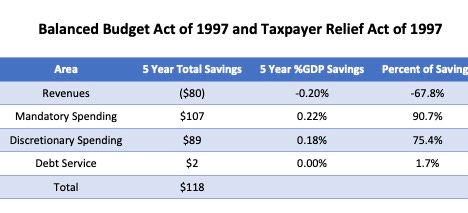

The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 & the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997

These two pieces of legislation were tied together for passage in 1997 and are considered as a pair here. This legislation was adopted under a Democratic president with a Republican House and a Republican Senate. It had the smallest deficit impact of the three bills being considered, only reducing the deficit by 0.2% of GDP. This legislation paired tax cuts – which added 0.2% of GDP to the deficit – with spending cuts of 0.4% of GDP, mostly aimed at mandatory spending. It’s included here because it seems representative of what a deficit reduction bill under unified Republican control might look like (there isn’t really a historical example of significant deficit reduction under a Republican trifecta in the post-Cold War era, though in the GOP’s defense that only accounts for 8 of the past 33 years). In this view mandatory spending would see more significant reductions, revenue would be static or decrease, and discretionary spending would fall somewhere in the middle. It’s worth noting that current commitments by former President Donald Trump and current President Biden to protect mandatory accounts makes it likely that cuts would fall more heavily on discretionary spending than what was seen historically.

Defense spending, again assuming a somewhat uniform breakdown of cuts within discretionary spending accounts, would see reductions of just under 2.7%. This would be the lightest touch of all three scenarios. However, the flip side of this is that with only roughly $312 billion in deficit reduction over five years, it is unclear if this legislation would be sufficient to actually address rising borrowing costs and restore stability to the market for US treasuries, prompting the need for additional rounds of deficit reduction.

Congressional Mechanics

The three above bills should provide a useful range of outcomes to consider when looking at future deficit reduction. However, it is reasonable to be skeptical of what sort of political coalition could arise to pass major deficit legislation and to think through how that might impact national security cuts in these scenarios. First, we should look at what type of partisan divide would accommodate a deficit reduction bill and second, we should consider how the various factions within the parties would drive these negotiations.

Two of the three case studies and the past two deficit reduction bills (the 2011 BCA and the Fiscal Responsibility Act from earlier this year) have been adopted under divided government. The last time one party adopted major deficit reduction legislation was the 1993 OBRA under the Clinton administration (last year’s Inflation Reduction Act should reduce the deficit slightly, but it is difficult to view that as being primarily deficit reduction legislation). It is reasonable to expect that the most likely outcome will be that the 2024 election continues divided government with the White House and at least one Congressional chamber being held by different parties. A divided government will demand compromise from both parties and likely mean that national security spending becomes a key part of bargaining and will be at risk.

In addition, the rise of the modern filibuster for almost all significant legislation has increased the salience of reconciliation legislation. This particularly type of budget activity has severe limitations but has been used by both parties to adopt a variety of bills over the past two decades, mostly increasing the deficit, but it could also be used to reduce spending.

Unified Democratic control in 2025 would also pose risks to national security spending, as the progressive wing of the party would likely push to reduce defense spending as part of any budget deal. Absent the countervailing force of needing to find votes from Republican budget hawks, this would likely be the worst outcome for national security toplines.

Unified Republican control in 2025 would result in legislation that is harder to forecast – it is possible that national security hawks would generally protect national security spending, but existing splits within the party over how to approach mandatory spending would make it hard for such legislation to result in significant spending. Such an approach would almost certainly exclude any attempt to increase revenue, putting further pressure on spending accounts to generate savings.

One key thing to keep in mind in this is that the geopolitics of the 1990s were far more conducive to significant cuts to defense spending. The end of the Cold War provided the United States with a “peace dividend” that the government eagerly took advantage of. From 1989 to 1996, nominal national security spending declined from $304 billion to $266 billion before resuming growth in 1997. The United States faced limited requirements for international deployments and no real peer competitors. The current geopolitical environment, with China aggressively arming itself and Russia fighting a hot war in Europe, is decidedly less conducive to national security cuts.

That being said, national security policy makers and industry players should not assume that the public is therefore behind growing the budget. A variety of polls indicate that Americans are fairly split on whether we are spending too much or too little on national defense. This is reflected in Congress, where the rise of defense spending skeptics on the right has created a bipartisan coalition that has pushed back on defense budgets and, in particular, spending associated with fighting in Ukraine. While there remains a sizeable majority in favor of current trends in defense spending, the coalition involved is weaker than it has been in some time.

Conclusion

In a marked change from the past two decades, the cost to service government debt is rising rapidly and putting real pressure on the federal budget. This increased cost, should it persist, will need to be met by Congressional action to reign in deficits and reduce the national debt. The last time we faced these conditions, there was a series of three pieces of deficit reduction legislation adopted over the course of a decade applying varying changes to future revenues and expenditures to address the debt. These solutions, if imitated in the next few years, would have significant impacts on national security spending. However, the domestic politics and geopolitical conditions that exist now are not what they were in the 1990s, and future deficit reduction could look very different from these previous bills. National security policy makers and industry must remain attentive to the growth in borrowing costs and engage early and often with governmental decision makers to ensure that their requirements are met in any future deficit negotiations.