The U.S. Navy is Losing the Arms Race

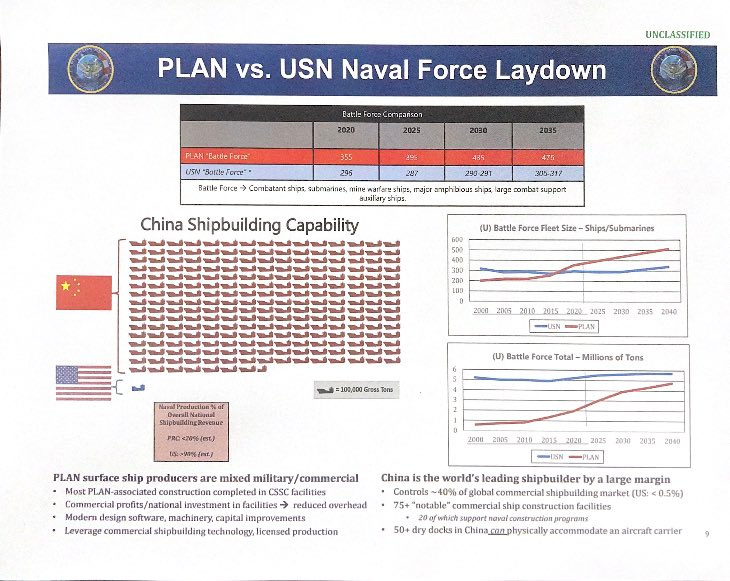

By 2040 the U.S. Navy may be smaller than the People's Liberation Army Navy both in terms of ship count and in terms of tonnage displaced.

I generally try to avoid being particularly political in these posts, but I’m going to set that aside because I am deeply concerned that the United States is sleepwalking into a situation where it will be unable to protect its many international interests and partners because it has failed to provide a Navy capable of preventing an opponent from controlling the high seas. It is clear that it is both too late and too expensive for the United States to maintain the degree of naval dominance it has enjoyed since the Second World War, but allowing the balance of power to slip too far against us would have a dramatic impact on our foreign relations and our economy. It is absolutely essential that Congress, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, and the White House come together to make radical changes to our approach to shipbuilding if we are to avoid catastrophe.

I’m not going to lay out all of the ample statistics undergirding how maritime commerce has been and continues to be a critical part of the lifeblood of America. I encourage you to read the long Atlantic piece by Jerry Hendrix I’ve linked to above if you need convincing. I’m just going to focus on this slide which I found floating around what remains of Twitter:

If I were still a Congressional staffer with any sort of involvement with national security issues, I would want to make sure my boss got a good, long look at this slide. It is not, to be clear, the most attractive piece of slide craft, but the numbers are presented plainly and they are alarming. Indeed, they should be shocking if you’re unfamiliar with the travails of U.S. Navy shipbuilding over the past twenty years. However, while we cannot change the past, we can try to improve our performance going forward. It is absolutely essential that we do this and, as evidenced by the dire numbers above, there is very little time to waste.

If I were still a staffer, I would also make a few recommendations to my boss in terms of what those next steps should be. Here are a few brief thoughts on potential actions that could be taken to reverse these terrible trend lines.

First, the Department of the Navy needs to own up to the fact that it is in a shipbuilding race with PLAN and react accordingly. There has been some progress on this front. In the FY 2023 National Defense Authorization Act, Congress created a “National Commission on the Future of the Navy”. The commission is tasked with, among other things, identifying what the size of the future fleet should be, a tacit admission that the DoD has failed to adequately address what the strategic goal of the Navy should be and what it will take to resource it accordingly. However, I think Congress must go further and should mandate that the Navy bring to it a plan within the next year to match the tonnage being built by the PLAN within the next five years. Bluntly put, previous ship-building goals have always been airy things with no real teeth or intent behind the. By creating a near-term requirement with crystal clear objectives, Congress can help to create urgency within the department and make it easier to hold people accountable.

Second, Congress should consider implementing a version of the CHIPS Act for shipbuilding. Versions of this legislation have bounced around for some time, but the success of the CHIPS Act in driving an expansion of US manufacturing should serve as notice that ambitious attempts to grow US shipbuilding capacity can be successful. National security advocates should lean into the recent revival in industrial policy to try to boost both defense shipbuilding and to revitalize America’s languishing commercial shipbuilding.

Lastly, and in recognition of the fact that investments in shipbuilding will take years to see fruit, the U.S. should also work closely with allies to engage and drive their shipbuilding capabilities. Japan and South Korea both have used aggressive industrial policy to protect their shipyards and we should seek to leverage their strengths whether through direct purchases of ships or through encouraging foreign investment in the United States. While there are risks that may be incurred through relying on facilities well within the range of China’s vast missile inventory, from a cost and near-term requirement perspective, there is much to be gained by working closely with our allies.

It’s worth stepping back and noting that the U.S. Navy, today, remains the most capable force on the seas. There can be no doubt of that. However, between the demands placed on our fleet by our far-ranging deployments (a cost the PLAN does not incur) and our anemic shipbuilding, we are at risk of squandering this most critical of capabilities. It is absolutely essential that we take steps to protect our Navy and that will require more focus, more money, and more oversight if it is to be successful.